In June 1940 CE, after the Wehrmacht had overrun continental western Europe, Britain remained as the sole enemy of Germany.

Hitler thought that the country would sue for peace, but it stubbornly refused.

Angered, he let the Wehrmacht draft plans for attacks on Britain's trade and industry

and also for an amphibious invasion, "Unternehmen Seelöwe", Operation Sea Lion,

though he kept the option of bombing Britain to the negotiating table as a reserve plan.

The seas surrounding the British Isles and the superiority of the Royal Navy prohibited a direct attack.

The Germans sought to tip the balance by achieving air superiority.

In July, after losing about 1/3 of its strength in the Fall of France,

the German Luftwaffe still had 1,300 combat-ready bombers, 300 dive bombers and 750 fighters at its disposal.

Almost all of the bombers were medium bombers and attack aircraft, built to support the army; the Germans were lacking in heavy bombers.

Most of its fighters were Messerschmidt Bf-109's, capable aircraft but without enough operational range,

so that they could remain above British soil only briefly before being forced to turn back.

Bombers had to halve their effective load and replace the other half with fuel for the return trip.

The pre-war focus of the Royal Air Force (RAF) had been on developing a fleet of strategic bombers.

It too had suffered losses in the Battle of France, about 1,400 aircraft, half of them fighter airplanes.

It had only some 450 fighters left to defend Britain and thus was severely outnumbered.

But the RAF also had built a network of 30 radar stations that together with spotters on the ground made a good early warning system.

The information was assembled at Fighter Command Headquarters, filtered, bundled and distributed to the air bases.

This Dowding system allowed British fighters to scramble at the last possible moment, beat off an attack and land, refuel and rearm before the next one arrived.

This was helped by poor coordination of the German attacks.

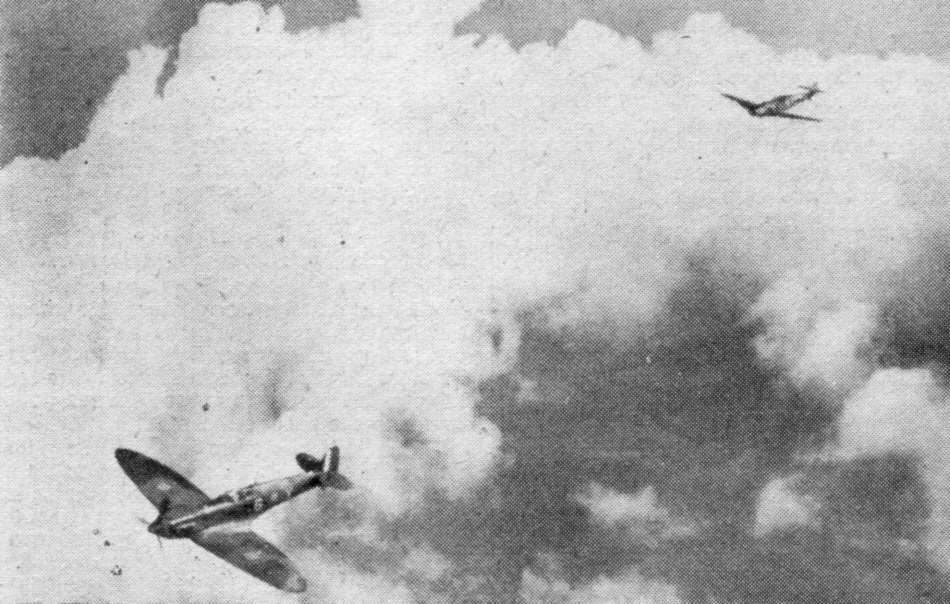

In combat, the Luftwaffe fighters flew in two-airplane sections that were more flexible than the British 'vics' of three.

However instead of hunting down British fighters they were forced to protect their bombers, which proved very vulnerable against fighter attack.

On the British side the RAF deliberately tried to avoid confrontations with German fighters and target the bombers instead.

The Luftwaffe countered by flying in formations that protected the bombers from several sides.

The British had the home advantage; almost all pilots who survived a crash could be back in action quickly,

while any German pilot who was shot down was likely to be killed or captured.

In late June the Luftwaffe started to skirmish with the RAF, trying to lure it out.

From mid July the focus shifted to attacks on ships, ports, airfields and industry.

The offensive strategies did not result in the desired effect, so German attacks were stepped up in August and the battle began in earnest.

By then the strength of the RAF was 570 fighters, 2/3 Hurricanes and 1/3 Spitfires, though only 70% were operational.

They were supplemented by some 1,800 anti-aircraft guns.

The Luftwaffe was down to 540 bombers, 320 Bf-110's and 810 Bf-109's, about 80% of them operational.

The 13th of August was labeled "Adlertag", Eagle day, implemented by five waves of airplanes, flying 1,500 sorties in total.

The aim was to knock out the RAF by destroying radar stations, airfields and aircraft themselves.

The RAF flew half as many counter-sorties and suffered 2/3 lower losses, 1/2 if only fighters are counted.

Though Adlertag was not successful, the Germans kept up the attacks for several weeks.

Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring pulled his vulnerable Stuka dive bombers out of the battle and strengthened fighter escorts.

After a few weeks the RAF still had a decent supply of fighter aircraft, but was running short on experienced pilots, having lost about 1/3 of them in the battle.

Yet the Luftwaffe too was suffering heavily.

On average it lost airplanes 1½ times faster than the RAF, while production of new aircraft was 2 times slower.

Pilots were lost even 2 times faster and were tired because the Luftwaffe did not rotate them in and out of battle like the RAF did.

Despite the attrition, the Luftwaffe could feed reserves into the battle and with hindsight seemed capable of wearing the RAF out.

At the time, German superiority was not so apparent and made its high command waver.

Starting from early September the Germans once again shifted the focus of the attack.

An accidental attack on London and subsequent retaliation by RAF Bomber Command on Berlin prompted Hitler to reply likewise.

The energies of the Luftwaffe were diverted from the air bases and onto London and other cities; the "Blitz" had started.

The air attacks damaged the cities, but allowed Fighter Command to recover its strength.

In the second half of September it inflicted severe losses on the Luftwaffe.

The Germans abandoned the Battle of Britain and with it Operation Sea Lion.

Instead they switched to a long campaign of nighttime bombing of Britain.

Bombing raids continued on and off into 1941 CE, when most Luftwaffe strength was directed east for Operation Barbarossa.

One of the reasons that the Luftwaffe lost the Battle of Britain because its earlier victories had made it overconfident, thus it underestimated the strength the RAF.

Others were the lack of range of the Bf-109's and the shifting back and forth between different strategies.

Perhaps most important, it just was not strong enough to overcome its enemy, which used the advantage of its strategic position well.

War Matrix - Battle of Britain

World Wars 1914 CE - 1945 CE, Battles and sieges